SPAIN, history

Part 1: Prehistory and Antiquity

Prehistory is the period during which no written historical record has been made, roughly 1000 BC.

Sima de los Huesos (the Pit of Bones), Sierra de Atapuerca.

In 1976, in the hills of Atapuerca, Northern Spain, an important archaeological find was made; three human teeth. Excavations eventually yielded 6,700 bones and teeth belonging to the skeletons of 28 human beings,

whose remains had been hidden under the hills for over 400,000 years. DNA research showed that they belonged to Homo Heidelbergensis, the common ancestor of the Neanderthal (Homo Sapiens Neanderthalensis) and the modern human (Homo Sapiens Sapiens). The Sierra de Atapuerca is the oldest excavation site of (pre) human remains in the world. Homo Heidelbergensis were hunters and lived between 600,000 and 200,000 years ago in Europe and Africa.

Neanderthals

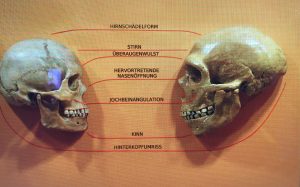

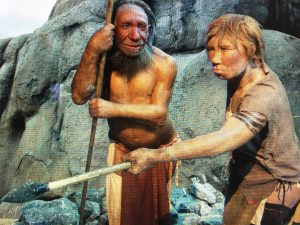

350,000 to 400,000 years ago, the Homo Heidelbergensis evolved into the Neanderthal in Europe and later the modern man in Africa. This evolution probably had to do with climatic differences between Europe and Africa, especially in the barren ice age. The Neanderthal was more sturdy and muscular than modern humans and also had a larger brain volume. They lived in Europe and the western part of Asia. About 40,000 years ago, modern humans migrated from Africa into Europe and lived together with the Neanderthals for several thousand years. We don´t quite know how peaceful this co-existence was or whether the modern human was responsible for the extinction of the Neanderthal, as has been the case with so many other species. The fact is that 2% of our human DNA stems from the Neanderthal. Peaceful or not, both types certainly had contact with each other.

350,000 to 400,000 years ago, the Homo Heidelbergensis evolved into the Neanderthal in Europe and later the modern man in Africa. This evolution probably had to do with climatic differences between Europe and Africa, especially in the barren ice age. The Neanderthal was more sturdy and muscular than modern humans and also had a larger brain volume. They lived in Europe and the western part of Asia. About 40,000 years ago, modern humans migrated from Africa into Europe and lived together with the Neanderthals for several thousand years. We don´t quite know how peaceful this co-existence was or whether the modern human was responsible for the extinction of the Neanderthal, as has been the case with so many other species. The fact is that 2% of our human DNA stems from the Neanderthal. Peaceful or not, both types certainly had contact with each other.

Gorham’s cave, Gibraltar

In the last ice age, the Neanderthals were slowly extinct and climate change certainly played an important role in this. The last ones probably lived in southern Spain. Until recently, it was generally assumed that the Neanderthals lived about 30,000 years ago. However, remains of Neanderthal tools in Gorham’s cave in Gibraltar show that they were still living in southern Spain some 24,000 years ago.

Cueva de Nerja

Homo Sapiens Sapiens, the modern man, left behind cave paintings that have shown to be 20,000 years old. Some well-known examples of these can be found in Spain: the famous paintings in the caves of Altamira (Cantabria, Northern Spain) and those in the Cueva de Ardales (Andalucia, an hour drive from the Costa del Sol). There are also some examples in the kilometers long caves in Nerja (Cueva de Nerja, Costa del Sol, Andalucia). The Neanderthals were not considered capable of such artistic expression so until recently, it was assumed modern man was responsible. Recent carbon dating revealed however, that these paintings are 43,000 years old and that the paintings (portraits of seals in the Mediterranean) are therefore likely to have been made by the Neanderthals. With this, the cave paintings of Nerja are the oldest discovered in the world and the only ones produced by Neanderthals. (Both pictures: Wikipedia).

Homo Sapiens Sapiens, the modern man, left behind cave paintings that have shown to be 20,000 years old. Some well-known examples of these can be found in Spain: the famous paintings in the caves of Altamira (Cantabria, Northern Spain) and those in the Cueva de Ardales (Andalucia, an hour drive from the Costa del Sol). There are also some examples in the kilometers long caves in Nerja (Cueva de Nerja, Costa del Sol, Andalucia). The Neanderthals were not considered capable of such artistic expression so until recently, it was assumed modern man was responsible. Recent carbon dating revealed however, that these paintings are 43,000 years old and that the paintings (portraits of seals in the Mediterranean) are therefore likely to have been made by the Neanderthals. With this, the cave paintings of Nerja are the oldest discovered in the world and the only ones produced by Neanderthals. (Both pictures: Wikipedia).

Modern humans have inhabited Europe for the last 20,000 years or more. About 8000 years ago, the influences of the Neolithic, the new Stone Age, arrived from Mesopotamia and Egypt to Spain. It is from this time that the Dolmenes de Antequera date. These megalithic (large tomb stones) in the province of Malaga, are more than 6000 years old and the area has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2016.

The role of hunting and gathering and thus the nomadic existence, decreased in the new Stone Age. Modern humans settled and dedicated themselves to primitive forms of agriculture and animal farming. The earliest remnants of this have been found mainly around Almeria where earthenware and sharpened stones, such as spearheads and axes have been dug up. In this area, the oldest walled settlement in Spain was found, dating back more than 4000 years.

From prehistory to antiquity (+/- 3000 BC – 1000 BC)

Southern Spain was rich in minerals and ores and in particular copper. Ties with civilizations from the eastern Mediterranean area meant a gain of metallurgical knowledge to emit bronze from copper and tin. These factors caused Spain to move relatively early from the new Stone Age (Neolithic) into the Bronze Age.

The original inhabitants of the Iberian Peninsula were warlike tribal people. The most developed Iberians lived in the South East, where contacts with Greek and Phoenician merchants and settlers resulted in a form of society that was common to the Greeks.

The great need for bronze among other peoples around the Mediterranean made southern Spain ( today´s Andalucia) an attractive trading partner. Communication with more developed cultures (the first Cretan Minoans who had contact with Egypt and Persia) also determined the development of an Iberian culture. In addition, trade settlements were established and merged, initially mainly Greeks, with the Iberian population. The Greeks might have founded the city of Malaga, although no Greek remains have been found to verify this.

Central and North Western parts were inhabited by more primitive societies living mainly from simple farming and herding.

A separate group lived in the Western Pyrenees and the South Western hills, the Basques. The Basques were also shepherds and lived as a tribe, with strong family ties and until the end of Roman times, they lived in relative isolation on the Iberian Peninsula. The origin of the Basque people and their language is still unknown. Are the Basques the original, pre-Iberian inhabitants of Iberia, or are they from elsewhere? The Basque language shows no relation to any Indo-European language.

Part 2: from Celt Iberians, Phoenicians, Romans, Visigoths and Mores to Catholics (1000 BC – 1492 AD)

Celt-Iberians

In addition to assimilation with Greeks, the mixing with Celts occurred between 1000 and 500 BC when the Celts arrived over the Pyrenees, entering the Iberian Peninsula and mainly settling in Northern Spain. Among other things, Ebyzos (Ibiza) was founded by the Celts (654 BC). There are still many remains of Celtic culture in Spain, such as the dolmen. (Picture: Celtic tradition in Santiago de Compostela, Galicia).

In addition to assimilation with Greeks, the mixing with Celts occurred between 1000 and 500 BC when the Celts arrived over the Pyrenees, entering the Iberian Peninsula and mainly settling in Northern Spain. Among other things, Ebyzos (Ibiza) was founded by the Celts (654 BC). There are still many remains of Celtic culture in Spain, such as the dolmen. (Picture: Celtic tradition in Santiago de Compostela, Galicia).

Phoenicia (Phoenicia) / Carthage (+/- 1000 BC – 146 BC)

Phoenicia was located in the area of current Lebanon, Israel and Syria. At around 1400 BC, after the Minoan empire collapsed, Phoenicia became the most successful seafaring and trading nation in the Mediterranean. In the Greek city-states, on the North African coast and also at the Spanish coast (Gadír-Cádiz) Phoenician colonies were founded.

The Phoenicians introduced grapes, olives (picture) and donkeys to Spain. The most famous Phoenician city- state was Carthago (in the present Tunisia and its inhabitants were named “Puni” by the Romans.

The Phoenicians introduced grapes, olives (picture) and donkeys to Spain. The most famous Phoenician city- state was Carthago (in the present Tunisia and its inhabitants were named “Puni” by the Romans.

Around 500 BC the Persians conquered Phoenicia and Carthage continued independently as an important power in the Mediterranean. Initially, Carthage controlled the south coast (Cádiz). By that time, Carthage plundered the city of Malaca (Malaga), which might explain the fact that no Greek remains have ever been found in Malaga.

Later, around the 3rd century BC, Carthage expanded its power to the South East of the Iberian Peninsula. The current Cartagena in Murcia (named by the Romans as Carthago Nova) was founded by Carthage because of the strategically located natural harbor and silver mines.

The Romans (206 BC – 476 AD)

In the third and second centuries BC, the Puni (led by Hannibal) fought three wars with the Romans. During the Second Punic War, when Hannibal travelled across the Alps with his elephants to attack the city of Rome, the Romans opened a second front in Spain where they defeated the Punis (206 BC).

Around 200 BC (2nd Punic War), the area belonging to the present Cataluña fell into Roman hands and the city of Tarracco was founded. Tarracco became very wealthy from agriculture, textiles and overseas trade. Tarracco was the capital of the Roman province of Tarragonensis.

In the present Tarragona many remains of this Roman provincial capital are still evident, including a large Roman city wall.

After the Third Punic War (146BC) Carthage was finally defeated, the once most powerful city on the North African coast was completely destroyed. Carthage became a Roman province (Africa!). After that, the Roman Empire conquered the Iberian Peninsula from the South East in the North Western direction. It would take another 200 years before the Romans had settled fully throughout the entire Peninsula, as the tribes in the North resisted fiercely.

Italica (10 km from present day Seville, partly on the territory of the current town of Santiponce) became the first Roman settlement on the Iberian Peninsula. A part of Italica has been excavated and is now an important archaeological site, which includes an amphitheater capable of hosting 25,000 people. Houses and mosaics can also be seen. Cartagena remained an important city to the Romans (capital of the province of Carthaginensis). The contemporary Cartagena contains, beside a large Roman amphitheater, many remains of Phoenician and Roman times. In 25 BC, Emperor Augustus founded the city of Emerita Augusta, strategically located around a ford on the Rio Guadiana River, which became the capital of the Roman province of Hispania Lusitania. (Merida is now the capital of the Autonomous Region of Extremadura). Many monuments from Roman times have been preserved in Mérida, including a temple, a theater, an amphitheater, houses, mosaics, and the magnificent bridge over the Rio Guadiana.

Italica (10 km from present day Seville, partly on the territory of the current town of Santiponce) became the first Roman settlement on the Iberian Peninsula. A part of Italica has been excavated and is now an important archaeological site, which includes an amphitheater capable of hosting 25,000 people. Houses and mosaics can also be seen. Cartagena remained an important city to the Romans (capital of the province of Carthaginensis). The contemporary Cartagena contains, beside a large Roman amphitheater, many remains of Phoenician and Roman times. In 25 BC, Emperor Augustus founded the city of Emerita Augusta, strategically located around a ford on the Rio Guadiana River, which became the capital of the Roman province of Hispania Lusitania. (Merida is now the capital of the Autonomous Region of Extremadura). Many monuments from Roman times have been preserved in Mérida, including a temple, a theater, an amphitheater, houses, mosaics, and the magnificent bridge over the Rio Guadiana.

Map: (from Wikipedia), Spain in Roman times. Added the cities Barcino (Barcelona, B), Tarraco (Tarragona, T), Valentia (V), Cartago Nova (C), Malaca (M), Antikeria (Antequera, A), Ronda (R), Spades (Cádiz, G), Hispalia (Sevilla, H), Italica (I), Corduba (Co), Emerita Augusta (Mérida, E), Segovia (Sg), Toletum (To), Salamantica (Salamanca, Sa), Olisipo (Lisbon, O).

This bridge (picture), El Puente Romano, constructed more than 2100 years ago is the largest preserved Roman bridge of antiquity and spans some 792 meters. It formed an important link between Lisbon and cities such as Cordoba and Zaragoza. The bridge has been restored a few times and remained in use as until the end of the 20th century.

Mérida is one of the largest archaeological sites in Spain despite the fact that it was almost completely destroyed by the Arabs in 713 AD. With her many, relatively well preserved monuments, Merida was placed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List in 1933.

Mérida is one of the largest archaeological sites in Spain despite the fact that it was almost completely destroyed by the Arabs in 713 AD. With her many, relatively well preserved monuments, Merida was placed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List in 1933.

Baetica (the approximate area of present day Andalucia) became a rich and developed province of the Roman Empire with Corduba (Cordoba) as the main city. Spain has its name (Hispania) and its languages (Castellano, Galician and Catalan) thanks to the Romans who also introduced Christianity. A large Jewish colony was also established during Roman rule. The current infrastructure of Spain was to a significant extent developed in Roman times when Toledo was the hub of all roads. This changed somewhat after the inauguration of Madrid as the capital. Well preserved Roman bridges in Cordoba, Salamanca and Mérida are todays witnesses of Roman presence in Spain.

The most famous, Roman, aquaduct in Spain is located in Segovia.

The Emperors Trajanus (98-117 AD) and Hadrianus (117-138 AD) were born in Italica. Under Trajanus, the Roman Empire reached its largest size. Although latter conquerors destroyed much of Roman culture, there are still many Spanish cities that have a Roman theater or amphitheater as its heritage and are symbols of “bread and circuses for the populous” as propagated by the Roman emperors . A great example of this in present time is the football club Betis (Baetica) Sevilla, which finds its most loyal supporters in the Triana district of Seville (named after Emperor Trajanus).

In the 3rd century, the Roman Empire slowly began to exhibit weaknesses and cracks. On the Iberian Peninsula, peace was disturbed by invasions of Germanic tribes from the north. At the end of the 4th century, the empire was divided into two parts, the West Roman (including the Iberian Peninsula) and the Eastern Roman Empire, of which the capital became Byzantium.

By the end of the 4th century, the Huns, having trekked from Eastern Europe and Asia, gave the impetus for the Migration Period. Just like the Romans, the Visigoths (a Germanic tribe) were now threatened. The situation caused a conflict between the Romans and the Visigoths on the Danube. Many Germanic tribes from northern Europe fled southward, over the Pyrenees and the Alps. The once militarily dominant West Roman Empire weakened by decadence, corruption, economic malaise and internal disagreements, could not resist the invasions of the Germanic people. In 476 the Visigoths plundered Rome, which brought an end of the once great West Roman Empire.

In the 6th century, the Visigoths also conquered most of the Iberian Peninsula, partly due to the weakened Romans. They also defeated other tribes for example the Vandals and the Suebi, who had already settled there and had made Mérida their capital. Baetica (Andalucia) as part of the (Eastern) Roman Empire, resisted until 622 when it was finally captured by the Visigoths. Toletum (Toledo) became the capital of the Visigoth Empire. The Eastern Roman (Byzantine) empire would exist until 1453 when the Turks conquered the capital Constantinople.

The Visigoths (476 – 711)

The Visigoth Kings of Hispania saw themselves as the rightful successors of Rome rather than destroyers of a part of the Roman Empire. They therefore granted themselves the same status and privileges as the former Roman rulers (who had been suffocated by their own decadence and corruption, among other factors). The Visigoth king surrounded himself with an elite of several hundred local families who got direct access to the court and indirect access to an aristocracy in possession of the largest estates in Hispania.

A partial merger between the Visigoth military elite and the socio-economic elite of Hispania slowly emerged within this aristocracy.

During the Visigoth period, the once so successful economy of South-East Hispania entered recession. In particular this was caused by the lack of powerful governance. The ruling elite and warlords were often involved in mutual disputes whilst suppressing the population who worked as slaves in order to finance the armies and estates. The Visigoth court was unable to maintain a fully-fledged army to try and control the internal fighting and struggled to keep unity and order. The king leaned more and more on the power of the warlords, which continually decentralized the actual power in the country. It should be noted that the Northern regions of Hispania were barely integrated into the Visigoth kingdom and were far behind the South East in terms of development and organization.

During the Visigoth period, the once so successful economy of South-East Hispania entered recession. In particular this was caused by the lack of powerful governance. The ruling elite and warlords were often involved in mutual disputes whilst suppressing the population who worked as slaves in order to finance the armies and estates. The Visigoth court was unable to maintain a fully-fledged army to try and control the internal fighting and struggled to keep unity and order. The king leaned more and more on the power of the warlords, which continually decentralized the actual power in the country. It should be noted that the Northern regions of Hispania were barely integrated into the Visigoth kingdom and were far behind the South East in terms of development and organization.

Gradually, the distance between elite and population increased. The Catholic Church was officially recognized in 589 when the Visigoth King converted. As the only institution in the Visigoth Empire with a clear organization and cohesion it was a loyal ally to the king. At the beginning of the 7th century the Church enjoyed the height of its importance and was recognized as the most prestigious scientific center of Western Europe. Monasteries were established which further expanded its influence. This was not difficult in a country where a large proportion of the population lived in structural poverty and every spiritual hope was welcome. By the end of the Visigoth period, the church already had a lot of real estate in the form of monasteries, churches and land providing substantial income. The population was largely marginalized and in many cases lived as slaves of landowners or soldiers for the warlords.

The Visigoth Empire eventually became severely weakened by internal tensions due to social contradictions between the upper class and the dependents and slaves. In the last century of Visigoth rule, the impoverished people regularly revolted. Furthermore, there were religious fundamental tensions between various Christian factions and the Jews for example, were suppressed and ruled out. In conclusion, it can be said that the Visigoths never succeeded to unify Spain, instead they weakened the country and made it vulnerable.

No monuments of any importance were left behind by the Visigoths, there is however a Visigoth Museum in Toledo.

Arabs (“Mores”, “Saracenes”)

From 661 the Omajjads controlled the Islamic empire. Faithful to the command of Mohammed to spread Islam, it conquered the Roman provinces in North Africa. In 710 Berber king Tarif led an initial raid on the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula (Tarifa). A year later in 711, 7000 Islamic Berbers from North Africa headed by their captain Tariq, crossed Gibraltar Strait (Jabal-i-Tariq, the rock of Tariq or: Gibraltar in Spanish). Picture: The rock of Gibraltar, in the background Africa.

From 661 the Omajjads controlled the Islamic empire. Faithful to the command of Mohammed to spread Islam, it conquered the Roman provinces in North Africa. In 710 Berber king Tarif led an initial raid on the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula (Tarifa). A year later in 711, 7000 Islamic Berbers from North Africa headed by their captain Tariq, crossed Gibraltar Strait (Jabal-i-Tariq, the rock of Tariq or: Gibraltar in Spanish). Picture: The rock of Gibraltar, in the background Africa.

The severely weakened Visigoth Empire was taken without much opposition.

The Arabs conquered Cadiz, Seville, Cordoba and Toledo within a year. In 713, the Damascus caliph called for the establishment of Islam in the conquered areas. In 722, with a relatively small army, the Visigoths defeated the oppressive Moorish armies at Covadonga, whereupon the Christian kingdom of Asturias emerged in Northern Spain. Asturias is the only part of Spain that has always remained catholic. This is the reason why the Spanish crown prince always carries the title “Principe de Asturias”.

The march of the Moors further North, was stopped after battles at Tours and Poitiers (732). Five years later, Charles Martel again defeated Islamic armies at Narbonne, which forced them to withdraw south of the Pyrenees.

The Emirate of Cordoba

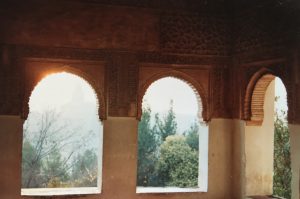

In 756, the Emirate of Cordoba was established which, with exception of the northern part, controlled the entire Iberian peninsula. Cordoba grew to great cultural and scientific prosperity to become a leading metropolis. In 756, Emir Abd ar Rahman I, started with the construction of the great mosque of Cordoba (the current “Mesquita”, picture). Cordoba then had more than half a million inhabitants, two hundred thousand more than in the early 21st century!

In 756, the Emirate of Cordoba was established which, with exception of the northern part, controlled the entire Iberian peninsula. Cordoba grew to great cultural and scientific prosperity to become a leading metropolis. In 756, Emir Abd ar Rahman I, started with the construction of the great mosque of Cordoba (the current “Mesquita”, picture). Cordoba then had more than half a million inhabitants, two hundred thousand more than in the early 21st century!

The Moors mainly focused on the development of cities, and no strong control was carried out in the rural areas which remained poor and underdeveloped. The northern border areas were relatively densely populated and most of the time there was free trade between the Christian north and the Islamic part of Spain. The northern provinces, which covered the whole of the north of the Iberian Peninsula, always remained independent.

The Catholic North

The formation of counties began in the 8th century; the Principality of Asturias developed in the Northwest, the Principality of Navarre (Basque country) in the western Pyrenees and from a fusion of several counties, to the South of the Eastern Pyrenees, Catalonia emerged. Charles the Great conquered Catalonia from the Mores in 801. Since then, Catalonia has always kept close contact with the Frankish empire.

Meanwhile the rest of Northern Spain maintained contact with Europe via the Pilgrimage Route to Santiago de Compostela (located in Galicia, then a part of Asturias). At the beginning of the 9th century, it was believed that the remains of the apostle Saint Jacob (Santiago) were washed up on the Galician coast. From the 10th century, Santiago de Compostela and her Basilica became increasingly important to Catholic pilgrims. The Moors, in an attack on the city, destroyed the Basilica. It was rebuilt in French architectural style during 1078-1124. In the 11th century, Santiago de Compostela became the most important pilgrimage town in Europe and a source of inspiration for crusaders. The first English pilgrims walked to Santiago around 1100. Santiago became the patron saint of the Reconquista in Spain.

Al Andalus, the caliphate of Cordoba

The Moorish occupants generally showed tolerance towards the conquered population and there was no extreme repression. There was a common trade language but the original residents continued to speak their own language and also to practice their own religion (Judaism and Christianity). Integration was limited with the different groups retaining their own identity but there was some mixing. Idealistically, “Al Andalus” (not only the present Andalucia but the entire Muslim-controlled area on the Iberian Peninsula) was a melting pot of religious-ethnic groups in which Islamic-Arab culture dominated but in which the populations for long periods co-existed with a reasonable degree of mutual tolerance.

The Moorish occupants generally showed tolerance towards the conquered population and there was no extreme repression. There was a common trade language but the original residents continued to speak their own language and also to practice their own religion (Judaism and Christianity). Integration was limited with the different groups retaining their own identity but there was some mixing. Idealistically, “Al Andalus” (not only the present Andalucia but the entire Muslim-controlled area on the Iberian Peninsula) was a melting pot of religious-ethnic groups in which Islamic-Arab culture dominated but in which the populations for long periods co-existed with a reasonable degree of mutual tolerance.

After Abd ar Rahman I (731-788), his descendants Abd ar Rahman II and III came to power. Abd ar Rahman III (912-961) declared himself Caliph and a large part of the Iberian Peninsula, the caliphate of Cordoba. After the death of the Caliph, the decay among its successors in the eleventh century culminated in a succession war that put an end to the political unity. The country was divided up into many smaller entities called “taifas”, that were continually fighting each other.

The Reconquista

The Reconquista, the reconquest of Islamic occupied Christian territory, which actually began in 722 with the battle at Covadonga, is given a firm impulse by this mutual division. However, the idea of a continuous, fierce Reconquista for many centuries seems a simplification. Part of the advance from the North was caused by population pressure in the northern kingdoms, especially in Catalonia, causing a migration through the relatively open border towards the South.

In the eleventh century, part of the northern border of islamic occupied area was still guarded by Christian mercenaries. Many struggles were also fought amongst Christian armies themselves, not really a sign of a unified effort against the Islamic enemy (1337: start of the100 year civil war).

The military weak Islamic Taifa empires could survive for a long time by accepting the protection of the now powerful Christian Northern kingdoms against payment. For example, the legend of El Cid (“The Boss”), Castilean nobleman Rodrigo Diaz ban be put in another perspective: he was not so much a Christian hero who fought to expel the Moors from Spain, he was a successful hirer who provided both services to Islamic as Christian rulers. Eventually, El Cid’s prince of Valencia’s taifa became very successful.

Almoravids, Almohaden

In 1085, Alphons VI of Castile conquered the city of Toledo, the former capital of the Catholic Visigothic Kings. The Almoravids, a strict religious Berber group from Senegal and Niger, were called for to help fight Alphons and thus landed on the Iberian Peninsula in 1086. These Berber soldiers were specialized in martial art, having trained in fortified monasteries in north-west Africa for the purpose of a holy war. Taifa’s declining power, decadency and their payments to unbelievers were a thorn in the eye to the Almoravids.

In 1085, Alphons VI of Castile conquered the city of Toledo, the former capital of the Catholic Visigothic Kings. The Almoravids, a strict religious Berber group from Senegal and Niger, were called for to help fight Alphons and thus landed on the Iberian Peninsula in 1086. These Berber soldiers were specialized in martial art, having trained in fortified monasteries in north-west Africa for the purpose of a holy war. Taifa’s declining power, decadency and their payments to unbelievers were a thorn in the eye to the Almoravids.

The Almoravids fought the armies of Alphons VI and later conquered Seville (“Geraldo”, photo left). Taifas were ended with and Al Andalus became part of the Almoravid empire that extended over North West Africa with Marrakesh as the capital. Under the repression of the more fundamentalist Almoravides, religious opposition was increasing and armed Christian orders arose. These orders played an important role in the acceleration of the Reconquista and their forts served to the continued monitoring of the conquered areas. The Almoravids soon fell into making the same mistakes as their predecessors thus giving way to new divisions and taifas.

In 1146 and 1147, Cordoba and Almeria were conquered by the orders and armies of French-Spanish noble men. Another branch of the Berber, the Almohades, came to the aid of the Almoravids and established a new caliphate. After much struggle with changing fortunes, Islamic rule lost the capital of Cordoba in 1236. (Mesquita). By the year 1250, the Reconquista, with the exception of Granada, was actually completed.

The Reconquista continued in varying intensity and ever changing front lines and successes over 770 years. It was finally concluded in 1492 with the surrender of Granada to Los Reyes Catolicos (the Catholic Kings, Isabella of Castilia and Ferdinand of Aragon).

The Reconquista continued in varying intensity and ever changing front lines and successes over 770 years. It was finally concluded in 1492 with the surrender of Granada to Los Reyes Catolicos (the Catholic Kings, Isabella of Castilia and Ferdinand of Aragon).